Twice Told Tuesday - The American Chaperone

Twice Told Tuesday features a photography related article

reprinted from old photography books, magazines, and newspapers.

reprinted from old photography books, magazines, and newspapers.

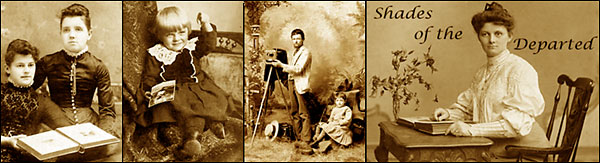

Ah, if only Paris Hilton and the other young women of fame and fortune in American today had the benefit of this book and the rules. Were any of your ancestors debutantes? The photograph is an example of what they might have worn. Check those old photos. A gown might not have been a wedding gown.

THE AMERICAN CHAPERONE

The question of the chaperone in America is peculiarly perplexing. The consternation of the hen whose brood of ducklings took to the water is a fit symbol of the horrified amazement with which an old-world "duenna" would be filled if she attempted to "look after" a bevy of typical American girls, with their independent—yet confused—ideas of social requirements in the matter of chaperonage.

In Europe, where social lines are distinctly drawn, a young woman either belongs "in society" or else she does not. In the former case she is constantly attended by a chaperone. In the latter case she is merely a young person, a working girl, for whom "society" makes no laws. In our country there is a leisure class of "society women," so recognized. If these alone constituted good society in America, we might simply adopt the European distinctions, and settle the chaperone question by a particular affirmative referring to these alone. But we reflect that our thoughts throughout this little volume are mainly for those who dwell within the broad zone of the average heretofore referred to. In this republican land no one can say that the bounds of good society lie arbitrarily here and there ; certainly they are not marked by a line drawn between occupation and leisure. The same young girl—after leaving school, at the period when society life begins—may be "in society" during leisure hours and in business during working hours.

In Europe, where social lines are distinctly drawn, a young woman either belongs "in society" or else she does not. In the former case she is constantly attended by a chaperone. In the latter case she is merely a young person, a working girl, for whom "society" makes no laws. In our country there is a leisure class of "society women," so recognized. If these alone constituted good society in America, we might simply adopt the European distinctions, and settle the chaperone question by a particular affirmative referring to these alone. But we reflect that our thoughts throughout this little volume are mainly for those who dwell within the broad zone of the average heretofore referred to. In this republican land no one can say that the bounds of good society lie arbitrarily here and there ; certainly they are not marked by a line drawn between occupation and leisure. The same young girl—after leaving school, at the period when society life begins—may be "in society" during leisure hours and in business during working hours.It is accounted perfectly lady-like and praiseworthy for a young woman, well born and bred, to support herself by some remunerative employment that holds her to "business hours." She may be a teacher, an artist, a scribe, an editor, a stenographer, a book-keeper—what may she not do, with talent, training, and good sense? And she may do this without being one iota less a lady—if she is one to begin with.

Now appears the complication. As a business woman, the self-reliant young girl does not need a chaperone. As a society woman, this inexperienced, sensitive, human-nature-trusting child does need a chaperone. She is, therefore, subject to what we may call intermittent chaperonage.

Business, definite, serious occupation of any kind, is a coat of mail. The woman or girl who is plainly absorbed in some earnest and dignified work is shielded from misinterpretation or impertinent intrusion while engaged in that work. She may go unattended to and from her place of business, for her destination is understood, and her purpose legitimate. She needs no guardian, for her capacity to take care of herself under these conditions, is demonstrated to a respectful public. The spectacle of a stately middle-aged woman accompanying each girl book-keeper to her desk every morning would be burlesque in the extreme.

The girl who is thus allowed to go alone to an office in business hours, sometimes thinks it absurd for any one to say that she must not go alone to a drawing- room, and she does go alone. Right here this independent girl makes a mistake. It is granted that the girl with brains and principle to bear herself discreetly during office hours is probably able—in the abstract—to exercise the same good sense at a party. But the conditions are changed to the eye of the onlooker. The girl who went to the office wearing the shield and armor of her work, now appears in society without that shield.

To the observer she differs in no wise from the banker's daughter, who " toils not." Like the latter, she needs on social occasions the watchful chaperonage that should be given to all young girls in these conditions. The woman who is in society at all must conform to its conventional laws, or lose caste in proportion to her defiance of these laws. She cannot defy them without losing the dignity and exclusiveness that characterize a well-bred woman, and without seeming to drift into the careless and doubtful manners of "Bohemia."

The fairy-story suggests the principle: Cinderella could work alone in the dust and ashes undisturbed; but the fairy-god-mother must needs accompany her when she went to the ball. In the best circles everywhere, at home and abroad, every young girl during her first years in society is "chaperoned." That is to say, on all formal social occasions she appears under the watch and ward of an older woman of character and standing—her mother, or the mother's representative. The young woman's calls are made, and her visits received, in the company of this guardian of the proprieties ; and she attends the theatre or other places of amusement, only under the same safe conduct.

The fairy-story suggests the principle: Cinderella could work alone in the dust and ashes undisturbed; but the fairy-god-mother must needs accompany her when she went to the ball. In the best circles everywhere, at home and abroad, every young girl during her first years in society is "chaperoned." That is to say, on all formal social occasions she appears under the watch and ward of an older woman of character and standing—her mother, or the mother's representative. The young woman's calls are made, and her visits received, in the company of this guardian of the proprieties ; and she attends the theatre or other places of amusement, only under the same safe conduct.Society to the young girl is May-fair. With the happy future veiled just beyond, she goes to meet a possible romance, and to traverse a circle of events that may haply round up in a wedding-ring. It is of the utmost importance that she shall not be left at the mercy of accidental meetings, indiscreet judgments, and the heedless impulses of inexperienced youth, which may effectually blight her future in its bud. A parent or guardian does a girl incalculable injury in allowing her to enter upon society life without chapsronage, and the unremitting watch-care and control which only a discreet, motherly woman can give to girlhood.

Men respect the chaperoned girl. Honorable men respect her as something that is worth taking care of; men who are not honorable respect her as something with which they dare not be unduly familiar—though they account it "smart" to be "hail fellow well met" with the girl who ignorantly goes about unattended, or with other unchaperoned girls, on social occasions. A girl must have an unusual measure of native dignity, as well as native innocence, always to escape the disagreeable infliction of either "fresh" or blast impertinence, if she has no mother's wing to flutter under.

This absolute condition of chaperonage exists during the novitiate of the young society woman. The requirement grows less and less rigid as the young woman grows more and more experienced, and learns to meet social emergencies for herself. That delicate ignoring of a woman's age which is shown in calling her a "girl" until she is married also permits her to be a chaperoned member of society until that event. But when obviously past her youth, it is no longer required that she shall wear the demeanor of a debutante. Nor does propriety demand her mother's constant presence, when years of training have taught the daughter her mother's discretion, and when the mother's own serene dignity looks out of the daughter's eyes.

We are proud of the ideal American girl. I mean the one who is essentially a lady, whether rich or poor; the one whose sterling good sense is equal to her emergencies ; the one who is self-reliant without being bold, firm without being overbearing, brainy without being masculine, strong of nerve—"but yet a woman." Let her be equipped for the battle of life, which in our state of society so many girls are fighting single-handed.

Instruct her in business principles; teach her to use the discretion needed to move safely along the crowded thoroughfare and to follow the routine of the office or the studio, trusting that with busy head and busy hands she may be safe wherever duty lends her tireless feet. But in her hours of social recreation, when she will meet and solve the vital problems of her own personal life, she needs a subtle something more; the mother's wisdom to supply the deficiencies of her inexperience, the mother's love to enfold her in unspoken sympathy, the mother's approbation to rest upon her dutiful conduct like a benediction.

Let no young girl regard this watch-care as a trammel placed on her coveted liberty. On the contrary, she will find that she has far more social freedom with the countenance of her mother's presence than she could have without it. And in after years, when her life has developed safely and happily under this discreet leadership, she will look back to her debut, and her first seasons in society, with profound gladness that—thanks to somebody wiser than herself—she has escaped the follies that have in more or less measure injured the prospects of her young friends who were too " independent" to submit to the restraints of chaperonage, and who, for lack of it, to-day find themselves to a relative extent depreciated in social estimation.

Source:

Morton, Agnes H. Etiquette. Philadelphia : Penn Publishing Co., 1893.

Photograph and drawing courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Labels: old photographs, old photos, vintage photographs, vintage photos

2 Comments:

In high school during the early sixties, I hated that my father insisted upon driving me to and picking me up after dances. Forty years later at a reunion I learned that all the local boys stayed away because of him. Looking at that bunch now, I'm glad.

ROTFL! This is one of the best comments I've received!

Having attended my reunion three years ago, I must agree. "Dad was right."

-fM

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home